My research focuses on (non-human) primates. ‘Non-human’ is in parenthesis, because I am not sure how helpful the differentiation is, as it implies some kind of human ‘benchmark’. Again, this brings me back to the title of this Blog ‘Human Enough’. We are all primates, we, being humans. A point which makes most people, that is, human people, quite uncomfortable in their primatey skins. Humans are animals too, but our membership to this species, carries with it immense privilege, drenched in power. Despite our sensitivity to the power we, as Homo sapiens hold over our furry, feathered or scaly kin, it is that very power, and our desire to ‘get somewhere’ in our activism and scholarly pursuits on behalf of, and for the animals, that ironically results in us, ‘getting in our own way’, in our mission to de-escalate the violence directed towards them. Before I get into that, I will indulge in some self-disclosure as to how I got here, and why I am sitting writing a blog about our relationships with animals.

I begin this post with an anecdote. An anecdote which throws me back to the 1980s, a time when I was a little person, strapped to my mother, while traipsing around a Zoo, on a leash. It was a harness actually, but regardless, I was restrained and tethered to my mother. I was a toddler who had not yet learned to contain my free will within the limits of what was considered socially appropriate in vast open spaces. At least for me, at the end of the day, my mother unclasped my harness and I was free again, as free as a toddler can be I suppose.This particular day at the zoo haunted me in ways which would shape my view of the world, and the animals within it.

It was his empty eyes. At first I didn’t see him. Up against a concrete wall, he sat slumped. If he had been human, it would have been described as ‘catatonia’. A behavioural ‘stupor’. In the DSM V, Catatonia is commonly associated with psychiatric manifestations such as PTSD and depression. He was a catatonic Orangutan. A catatonic Orangutan sitting in shredded newspaper. Of course I did not have the intellectual capacity then to understand the violation of rights that was happening here. But I did have the empathy to understand that this creature, was barely existing. I remember my mother pulling at my leash, as if to avert my eyes from the misery which was reflected in his. I know the sun was shining that day, but oddly, my memory of the Orangutan, is that of complete darkness, his massive body obscured by rusting bars and shadows. As my mother dragged me away, I remember asking her ‘what was that’? that. I remember trailing behind my mother, my small body feeling heavy with this sense that I had just stumbled across something I should not have seen, something that I did not understand. A shameful secret. A skeleton in a closet. Today, about 30 years later, I have finally found my way back to him, the ghost of that catatonic Orangutan. I quit my job and moved interstate to study primatology and completed research which looks at psychological wellbeing in great apes living in zoos. I often think about my memory of that day. Out of interest, I googled the history of orangutans in zoos in Australia during the 1980s. Anecdotal, non-academic articles of the time do not appear to reflect what I believe I saw that day. Instead, I read about Orangutan males who lived in social groups, in enriched conditions in zoos. Maybe, just maybe, I visited on a bad day. Maybe, my young mind, harboured an over-active imagination. Whatever the case, it matters little. What I do know, is that there was not a tree or another Orangutan in sight. What I do know, is on that day, I looked into vacant eyes.

The point to this anecdote, is that we all have one. Most of us pursuing Human-Animal studies, and/or activism, experienced some kind of ‘turning’. An animal we encountered. An animal that changed us. An animal with whom our interaction was too fleeting, or traumatising. An animal to whom we ‘owe’ something. A debt to re-pay. An acknowledgement of their existence, to the life they lived, or to the life which was robbed from them.

Since then, I have seen that look in other animals; in dairy cattle who have given up calling for their calf, in battery hens who have dissociated from their hellish existence, in fish who float bloated in tanks, in humans who are numbed to their own psychological pain.

Several months ago, I attended my first human-animals conference. I was looking forward to immersing myself in an equal love and respect for all creatures, with a robust discussion about how we can all work together to advocate for equality beyond humanity for all living beings. As a chicken loving, anti-whaling, cow-cuddling primatologist, I navigated the heaving menagerie of animal advocates. Great Apes were on the bill, not the head-lining act, that belonged to the factory farmed animals. Fair Enough- their voices are important too, and very little heard . Great Apes don’t need to be ‘up in lights’, they already have the lime-light. I get that. However, the point I would like to make, is that Great Apes, along with other mammals, have been slapped with the label ‘charasmatic mega-fauna’. Labelled by association. Their association with us. It is this belief, held by some (not all) animal rights advocates, which permeated some (not all) of the conference sessions I attended. In one particular talk, which focused on Great Ape and human communication, the air felt heavy. At first I didn’t understand what was underpinning this, until finally someone put up their hand and announced, that by focusing on Great Apes, we are only reinforcing a human-oriented hierarchy in which only those animals, in whom humans can see themselves, are worthy of having rights attributed to them. Apparently this is a slippery slope. If Great Apes are recognised as having rights, then a greater chasm will separate them from all the other creatures, and thus, all other creatures from rights. As I sat in the audience, I felt embarrassed. I think I actually blushed.I felt shame. Shame, that in some way I was contributing to the oppression of another being. Shame, because I had never really questioned my commitment to advocating for the rights of Great Apes. Why would I? My voice for Great Apes, in my life, has not silenced my voice for the rights of other animals.Whilst researching Great Apes, I would also stand in front of Parliament House to protest Live Export. On weekends I sold second hand clothes at the local trash and treasure markets. Any money I made was donated to Animal Protection groups. My point is not martyrdom, but the detrimental effects of assumptions. Have we not learned from history, that ‘us’ and ‘them’, does not end well in any social movement. I drove away from that conference feeling like ‘we have been here before’. Homo sapiens that is. Here being a phenomenon in which people claw each other down, in order to stop others, ‘the other’, from getting somewhere. Somewhere else. This all sounds very dramatic, I know. Dramatic enough and frequent enough to have a name. Lateral Violence.

Lateral Violence is a phenomenon that occurs in marginalised communities, where the ‘oppressed’ become the ‘oppressors of each other’ (Kwey Kwey consulting). Lateral Violence is observed in Indigenous Communities, particularly described in First Nation peoples of Canada and Australia. In my work with Aboriginal communities in Australia, Elders share the story of ‘crabs in a bucket’ to describe Lateral Violence. They say to imagine a bucket full of crabs that a fisherman has caught. Next to the bucket is a pot of boiling water. The bucket is bustling with crabs climbing all over each other, desperately trying to climb out to avoid certain death. But every time a crab makes its way to the top of the bucket, and can taste freedom from death, the other crabs claw it back down with the rest of them.

I wondered in what other realms Lateral Violence existed. In researching this post, I came across articles stating that beyond Indigenous communities, Lateral, or Horizontal Violence is common in the nursing profession. Apparently it does happen in activist communities. While ‘trying to save the world’, we can be ‘extremely cruel to one another’ (Blog: Activist Communique: Activists really know how to hurt one another). There is no reference to this phenomenon in the realm of Animal Activism,and I wonder if this is simply because we don’t recognise it.

In the social movement, historically, Lateral Violence has been rife in the Women’s Liberation Movement. Feminists have made accusations of classism, racism, homophobia, elitism, careerism, and male identification. In the Animal Rights movement, there are accusations of speciesism, elitism, apathy and anarchism. In the early days of the feminist movement, the ‘quest for egalitarianism was so strong that it became confused with sameness‘, a sense of competition, scrambling crabs, which ultimately held back the movement.It has only been my exposure to this concept in my other life, working with marginalised Homo sapiens that I recognised this phenomenon potentially occurring on a smaller scale in the Animal Rights Movement. In reference to the bid for Animal Rights, is the fear of success for one species over another, actually damaging the progress for all animals? Besides the individuals who are harmed, Lateral Violence, if it does exist, is most likely harming the entire movement as seen in other social rights arenas.

Substituting the Human Rights Model as proposed by the Australian Human Rights Commission, into that of the Animal Rights Movement, there could be the potential to move the equality of rights for all animals, beyond humanity.

Before the Animal Rights movement can be successful, we need to build a more reconciled Animal Nation:

a) between the Animal Rights Movement and the broader Australian community

b) between the Animal Rights Movement and the Australian Government AND

c) between the Animal Rights communities, cliques and tribes (ie- the dog people, the rabbit people, the battery hen people, the Great Ape people).

There are factions within the Animal Rights Movement. Abolitionists versus Welfarists. Conservatives versus Anarchists. The hen people versus the Great Ape people. The scholars versus the activists. The vegans versus the vegetarians, and (gasp), meat-eaters. Like the Human Rights Movement, the Animal Rights Movement faces many challenges, but some of the harm might eventually come from within our own community. Government and Industry will continue to operate in a system which fosters lateral violence and subsequently, any progress made will only come of strong and genuine unity within the animal rights movement (and to expand this idea further), between social movements, harnessing strength in intersectionality and interdisciplinary endeavor.

” When we are consistently oppressed, we live with the great fear and great anger, and we often turn on those who are closest to us” Richard Franklin, ( quoted in Chapter 2: Lateral Violence, Australian Human Rights Commission).

Colonisation underpins both the Human and Animal Rights Movements. Colonising powers (White, Straight, Male, Human) position themselves as ‘more than’, ignoring the basic rights and cultural identity of those it has power and control over (Un-White, GLBTI, Female, Animals). What chance then do animals have, when the very movement that seeks to protect them engages in gossiping, jealousy, shaming, bullying and conflict? The very elements which have hindered progress in other areas of social movement.

“Lateral Violence comes from being colonised…being told you are worthless and treated as being worthless for a long period of time. Naturally you don’t want to be at the bottom of the pecking order, so you turn on your own” (Richard Franklin, quoted in Chapter 2: Lateral Violence, Australian Human Rights Commission). It doesn’t take much of a leap to see the connection between natural dominance hierarchies in animal colonies,’red by tooth and claw’, and that as it plays out in human communities and social movements, specifically.

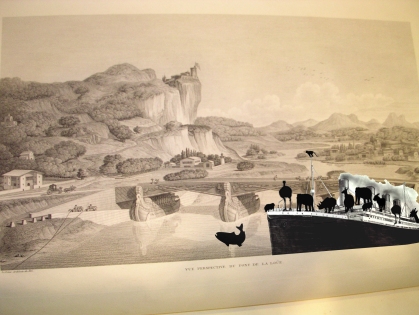

This is what I see occurring in the Animal Rights Movement. The ‘colonised’, in this case, the Animal Rights communities, recognise the oppressors within their own movement. It is my belief that all species can fall victim to Lateral Violence in the Animal Rights Movement; the rabbit people versus horse people, the cane toad people versus chicken people, the whale people versus the factory farming people. Lateral Violence will have a detrimental effect on the campaign for the recognition of rights for animals. I have reflected a lot on the response to the inclusion of Great Apes in human-animal studies. In writing this, I want to acknowledge the reality that Great Apes are a charismatic mega-fauna, and that other, lesser-known and smaller (less aesthetically pleasing) animals pale into insignificance in their ‘campaign to matter’. Having said that, I would also like to make the suggestion that perhaps (some) Animal Rights activists recognise the oppressor in the familiar faces of their Great Ape kin. Because Great Apes are so like humans, it appears there is a shared view that they don’t deserve or require the same degree of help, compared to those animals in which humans do not see themselves.It is ironic, that the reason Great Apes are suffering, that is, due to their human-ness which; fuels the pet-trade, their use in the entertainment industry and their exploitation in medical laboratories, is the very same reason that their voice is challenged in the Animal Rights Movement. To me, it almost feels as though the suffering of Great Apes is considered by some, as ‘less than’, simply because of their phylogentic closeness to humans, to the oppressors, and the associated application of a ‘moral status’. A status they did not ask for, by the way. How is it that our own propensity to project ‘human-ness’ onto another creature can interfere with their right not to suffer, simply because we ‘fear’ that this will impede the status of other animals, less ‘like’ us? This is counter-intuitive to me and makes me pose the question ” Is there enough room on the Titanic for All animals, or just a select few”?

I actually do not know the depth of Lateral Violence in the Animal Rights community. But I do suspect it exists.My application of this framework to Great Apes, is just one example. Perhaps what the Lateral Violence framework can provide, is a context to the factions we know exist in the Animal Rights Movement, and a way forward. How widely spread it is, I do not know. I would be very interested to hear the views of others. I am not being explicit,but instead, respectfully putting an idea out there for consideration and conversation.

For this to work, and by ‘this’, I mean, advocating for the rights of all animals, we Homo sapiens need to play in the sand-pit together- (com)passion uncompromising. A sand-pit large enough for the hens to ruffle their feathers and stretch their wings, for the pigs to roll around and exfoliate their hides, for the elephants to lie down and cool their massive bodies, for the turtles to dig deep and lay their eggs, and for the gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and orangutans to stretch out their legs and feel the sand between their toes.

Animals and the Titanic. Image source: Super Von Erlach’s Blog (wordpress)